I love how Doris Kearns Goodwin and Laura Hillenbrand explore American history through clear and clean prose that emphasizes strength forged by adversity. I started with “Team of Rivals”, but “Leadership: In Turbulent Times” is emerging as my favorite from Goodwin. Written in the companionable prose that makes Goodwin’s books surefire best sellers, “Leadership: In Turbulent Times” recounts the lives of Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson. Far from hagiography, Goodwin often resists the urge to glean pat lessons or rules from the past and allows herself to savor the stubborn singularity of each moment or personality and lets the reader find the grand themes across these four men.

It was a great surprise to find four of the most interesting presidents profiled in one book in a way that I could compare and contrast their stories as told against a backdrop of hardship. I’ve always a special love for Lincoln, followed by Teddy Roosevelt. The former for his deep well of wisdom and both for their moral courage. While I know that everyone’s story rests on a fabric of painful experiences, these leaders were tested by truly epic events and rose past the challenge to shape our country for the better. One reason I love reading Goodwin is her ability to present subtle, complex studies of her subjects’ personalities and to show how they interact with their times. Most remarkably, she renders her characters with a personal depth and intricacy that not all academic historians seek to attain.

“The story of Theodore Roosevelt is the story of a small boy who read about great men and decided he wanted to be like them.” There is a reason these specific presidents seem to monopolize the names of my kid’s schools. Aside from Johnson, whose Vietnam war tarnished his reputation, the other three were used to regale young readers with stirring tales of their exploits. There is a time-honored tradition of exalting any nation’s leaders, but there is a unique american deliberateness to using our presidents to forge the next generation of virtuous leaders. Goodwin joins this time honored tradition as she seeks to purvey moral instruction and even practical guidance to aspiring leaders through the stories of four exceptional American presidents.

In reading this book, I discovered that Goodwin has already produced full-length studies of each of these men, starting with “Lyndon Johnson and the American Dream” (1976) and continuing through “No Ordinary Time: Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt: The Home Front in World War II” (1994), “Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln” (2005) and “The Bully Pulpit: Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and the Golden Age of Journalism” (2013).

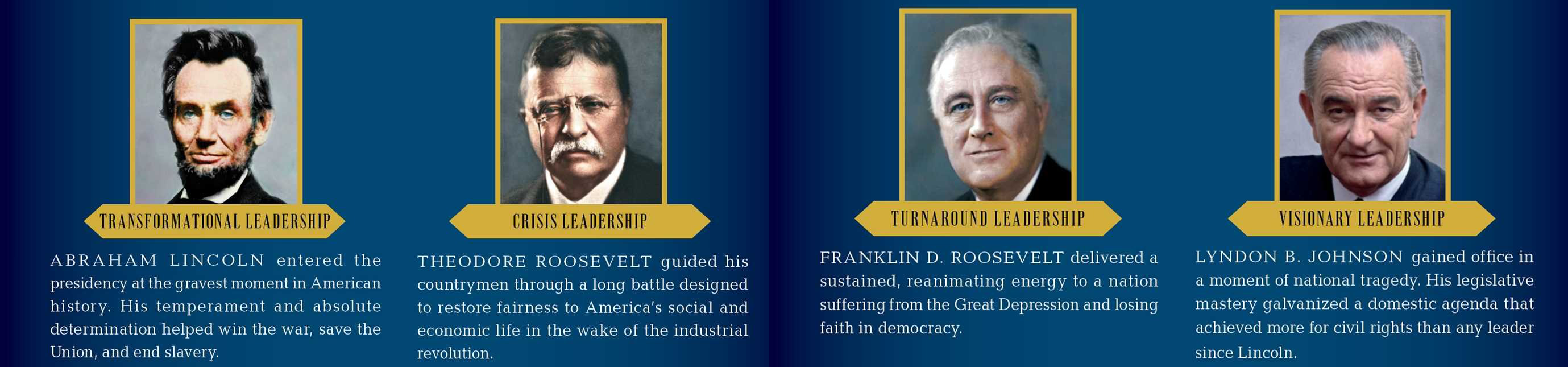

This book however, has a greater purpose than biographical. Here she forsakes the strict confines of biography for the new domain of leadership studies. These studies are routinely taught in business schools where they are geared toward would-be or midcareer executives and often focused on imparting useful lessons to apply in the workplace. In this case, Goodwin uses this angle to understand the formation of her subjects’ characters and how their most notable qualities equipped them to lead the country during trying times for each president personally and more broadly in the nation they led.

To accomplish this, she follows a specific recipe for exploring each character’s leadership. The first section features four chapters, one on each man’s boyhood and early influences; the second part, also comprising four chapters, dwells on early-adulthood traumas that tempered their flaws and bred resilience; the third part spotlights the chastened leaders in their crucibles of crisis; and an epilogue lightly glosses their legacies. In each man’s case, the setback is a prelude, a learning opportunity, a character-building experience: Abraham Lincoln as a young man withstood a depression so severe that friends removed all the sharp objects from his room; Theodore Roosevelt saw both his mother and his beloved wife die within a day; Franklin Roosevelt was stricken with polio; and Lyndon Johnson lost his first race for the Senate, throwing him into a depression of his own. I found it refreshing that her aim in telling these stories is not for their own sake but to establish certain central themes of skillful democratic leadership. It was also a small feat that despite the overarching steeled-by-adversity template into which she wedges these stories, each retained its own intrinsic and uniquely personal drama. Goodwin summarized this with: “There was no single path, that four young men of different background, ability and temperament followed to the leadership of the country.”

Gold needs fire. Tribulation produces wisdom. Growth requires pain. And greatness can flourish despite our leaders flaws and the deepest depths of national emergency.

While focusing on one president would have placed more emphasis on the person, exploring the variety and peculiarities among the four presidents took me out of each of their lives into a larger context. Each subject had common traits: preternatural persistence, a surpassing intelligence, a gift for storytelling. However, it is the differences among them that are most interesting. For example, where Abraham Lincoln grew up under the discipline of an austere and dominating father, who would destroy the books that his son loved to read, Franklin Roosevelt thrived under the trusting indulgence of a loving mother. In contrast to Theodore Roosevelt, whose curiosity led him to immerse himself in pastimes like studying birds and other animals, Lyndon Johnson “could never unwind,” channeling his manic energy into his ambitions. All this forced me to admit that the only safe generalization is that one can’t really generalize.

Goodwin’s honest narrative connects you with the real person. President Lyndon B. Johnson was grandiose and narcissistic who missed the opportunity to be remembered as a civil rights champion by his over reliance on letting his generals lead his foreign policy. Lincoln’s well known depression was on full display; but I was pleased to discover how his mordant wit reflected a deep stoicism and was left to determine this was why the weight of his melancholy didn’t derail his career.

Franklin Roosevelt, known broadly for his cheerfulness, possessed a fierce, even ruthless ambition. Her account of his drive to conquer his polio so that he could traverse the Madison Square Garden stage at the 1924 Democratic convention exemplifies her talent at bringing personality to life not through didactic exposition but through well-wrought narrative. She describes Roosevelt preparing for his convention walk by measuring off the distance in his library in the family’s East 65th Street house, then digging into his teenage son James’s arm with a grip “like pincers,” as he practiced hoisting his inert, braced legs across the room. At the convention itself, Goodwin recounts the tension in the arena as Roosevelt triumphantly hauled himself across the stage, on just his crutches, to seize “the lectern edges with his powerful, viselike grip” and flash his beaming smile to the cheering throng.

Pain, weaknesses and challenges didn’t detract from their leadership, but became the central message. Gold needs fire. Tribulation produces wisdom. Growth requires pain. And greatness can flourish despite our leaders flaws and the deepest depths of national emergency.

Leave a Reply